The following notes and images were part of a talk that I delivered on behalf of Works Progress Studio at the Con/verge event put on by Impact Hub MSP on November 17th, 2015.

—

Thank you to the organizers and sponsors of tonight’s #ConvergeMN event for inviting me here. It’s always a privilege to share thoughts and ideas in a space like this, with a group of people actively working to improve lives and communities.

I want to start by saying a few things about the concept of innovation & social impact. Sometimes we assume when we gather around innovation orsocial entrepreneurship or changemaking that we’re all on the same page about what these things mean, or why they’re important. We might assume that we all see the world and the value of creative and entrepreneurial work through the same or similar lenses.

But it’s not that simple, right? Especially when we’re talking across disciplines and communities. We come to these ideas with points of view that are not just based on our professional roles and achievements, but also informed by our life experiences, our formal and informal educations, and the ways we identify as individuals, communities, and cultures.

In other words, our subjectivity matters. Our unique experiences and perspectives are an important consideration when talking about the work we do in the world, and especially about why and how we do it.

I tend to be most interested in where someone is coming from. I want to know what that means about how they see the world, and what they believe, more than I want to know about their big ideas or what they think other people need.

And I think this is an ethic that I’m trying to bring forward through the projects I create. Our differences and commonalities matter. Bringing those differences and commonalities to the surface is where our potential to collaborate really exists.

To Change Everything, Start Anywhere. I like this quote. I first heard it from an artist and activist I know who is part of the Million Artist Movement. Million Artist Movement is group of artists and activists working to dismantle oppressive racist systems against Black, Brown, Indigenous and disenfranchised peoples.

And since we’re here to talk about innovation, I want to recognize the innovative activists, artists, community residents, and especially the young leaders with Black Lives Matter and other social justice groups, who right now are occupying the 4th Precinct headquarters of the Minneapolis Police Department, demanding footage taken in the recent Police murder of Jamar Clark. These innovators are using direct action to change systems now. I can’t come into rooms like this anymore without acknowledging the transformative things happening just outside these walls.

Million Artist Movement pointed me toward an essay, “To Change Everything: An anarchist appeal” that you can download from the link in the bottom right of the screen. It resonates with me, because when people ask me why I’m an artist, or why I work in the ways that I do, I always want to say, “To change everything!”

That seems like an impossible goal, but I really do mean it. Whatever I’m doing, in my own small way, I hope I am supporting larger collective efforts to change the very paradigms and systems that influence so much of our public and our private lives.

To me, that’s what innovation means. It doesn’t mean just coming up with cool new products or ideas or programs or organizations, and marketing those to funders or investors or customers, if those “innovations” only shore up the systems that are failing us — those social hierarchies, inequitable economic systems, and the environmental thinking that treats every thing and person as a resource toward endless growth and consumption.

To really innovate, I think we need to change those systems, and also imagine entirely new ones. And the good news is we can start anywhere.

We can start with ourselves. I’m an artist and designer and arts organizer. That’s the creative realm I live and work in, the anywhere to my everything. I work most often as Collaborative Director of Works Progress Studio.

This image is a collage from some of our projects. Specifically, Works Progress collaborates with other individuals and organizations to create social spaces — as well as public art, design, and media projects — usually at the edges and intersections of disciplines, places, and communities.

Most of the time I work in partnership with my husband and Works Progress Co-Director Colin Kloecker, though I also collaborate with lots of other artists and creative folks. A lot of our work concerns social and environmental ecology. Most of the time my role is to convene, to connect the dots, and to catalyze new collaborations. I‘m also an advocate for the creative thinkers and makers and doers all around me.

This slide is the result of an exercise we did trying to map our creative process. As you can see, it’s pretty messy, but what I learned in trying to see it as a whole is that we spend a lot more time and energy on “Research & Development” than anything else.

Collaborative Public Art and Design, Rooted in Place and Purpose. This is one way we describe what we do. Not placemaking, which is a term I don’t like very much, but collaborative public art and design that is rooted in place, and purpose. What purpose? I’ll get to that.

But first, I mentioned that we spend a lot of time on R&D. This is something that folks outside of the arts might not realize is a critical part of any artist’s creative process. We need space for questioning, experimentation, making connections, and making sense of what we learn and experience in the process.

When we talk about working across disciplines — for example, artists working with scientists or environmental organizations or Cities — this questioning and experimenting space is even more critical, because there’s a lot we don’t know about each other and the world as we see it through the prism of our practices. And we may need some help with translation.

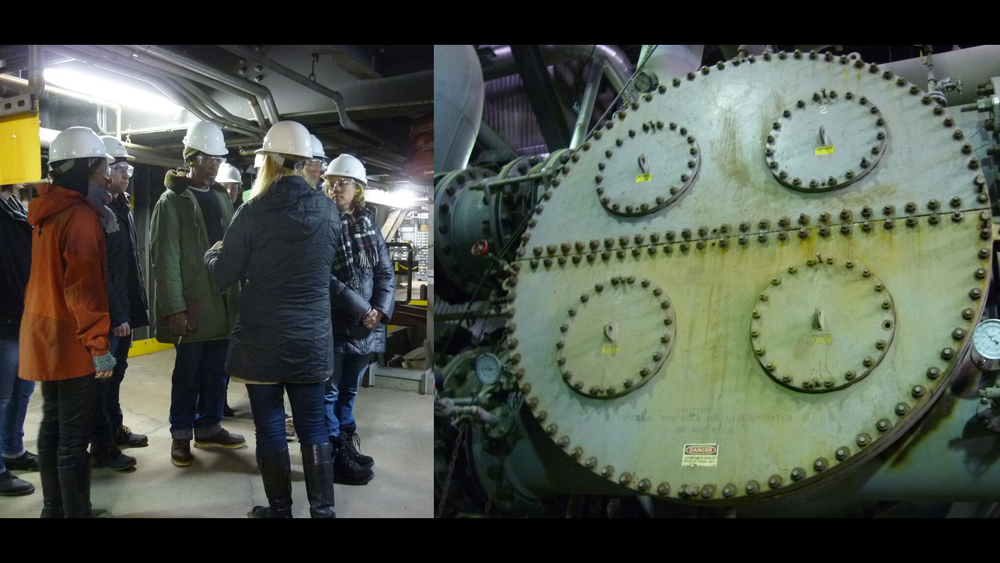

City Art Collaboratory is a research & development fellowship for public artists and science professionals to build relationships and explore collaborative possibilities around place and environment.

The Collaboratory program grew out of the visionary art and environment programming of the non-profit organization Public Art Saint Paul, and is formally a project of PASP and partners. My role as the Director of the Collaboratory has been to help shape our collective experiences, and to be a matchmaker and champion of other people’s projects.

Collaboratory artists and scientists are supported with a modest stipend, given access to new cross-disciplinary connections through a series of field trips and workshops, introduced to City systems and the environmental issues that those systems touch, and then asked to imagine possibilities, including publicly-facing art and engagement projects. Over time, the group builds relationships and collaborations organically, and these spin out into the world through new and existing work.

Here we are at Bruce Vento Nature Sanctuary, learning about Dakota places and place names, as well as their meaning, and discussing the ecological restoration and future of this former industrial site.

And here at the City of Saint Paul’s Street Maintenance division, learning about snow plowing, salt and sand, and how the City deals with weather and Climate Change.

And at District Energy, a sustainable heating and cooling plant on the river bluff in Downtown Saint Paul.

This is also District Energy, two years after our Collaboratory Field Trip.A group of artists have been working with the utility to create a public project that will help people see and understand our energy system in a different way. That project — The Plume Project — actually kicks off tonight and will feature multimedia artistic projects and projections on the steam plume through January, though there is already interest in replicating the project in other places around the globe.

Can We Drink the Mississippi River? Another project that really stems from this Collaboratory way of thinking is one I’m involved with as an artist. It began when a field trip led me to ask this question, in all earnestness: What would happen if we drank the water that flows through our Twin Cities? I started talking to the other artists and scientists and environmental advocates I know about this, and realized how fortunate I was to have access to their expertise in a social one-to-one way. I wanted more people to be able to have that experience

Can we drink the river? One answer is that we already drink the river every day. If you live in the Minneapolis or Saint Paul, your tap water comes from the Mississippi. As you can imagine, that system has a really great story, and touches on many others.

We started this project called “Water Bar” to introduce people to their water system, and to some of the researchers, public employees, policymakers, and environmental activists who are working to maintain — and also to transform — this particular system in light of some of the issues that we’re facing as a society. Rather than tell you what that is like, I’ll show you a quick video.

LINK TO VIDEO: TV Takeover Water Bar

Early on in the project, we looked for ways to help Water Bar visitors think more deeply about this everyday experience of drinking water.We created these flight trays that folks could use to write down tasting notes to compare with friends, which is fun and a bit silly. All of this lent itself to a social atmosphere where people felt at ease, where they could really question their own experiences and assumptions, asking the scientists and policy makers and activists about their work too. In other words, they could start to see a really complex system and their place in it, and could begin to imagine other possibilities.

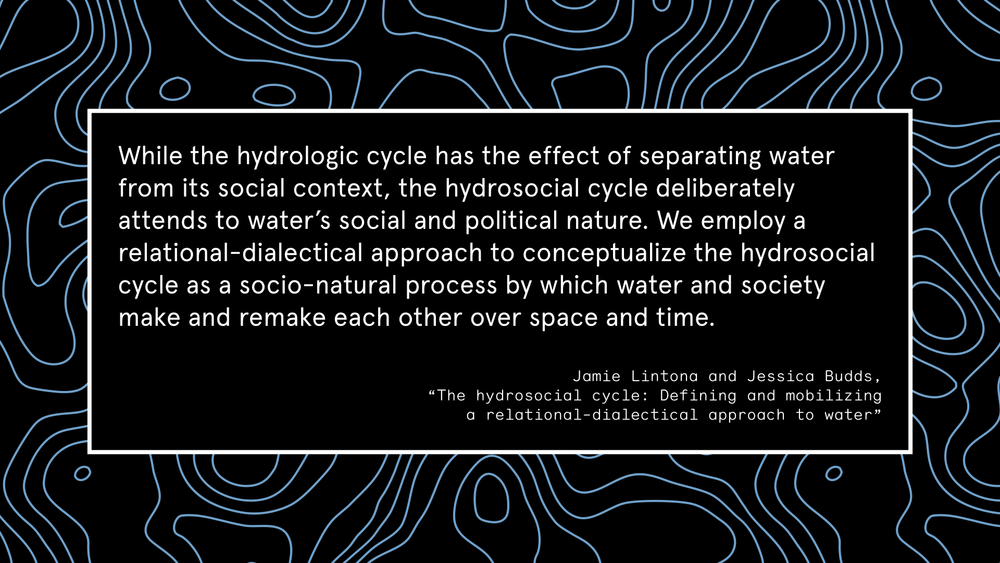

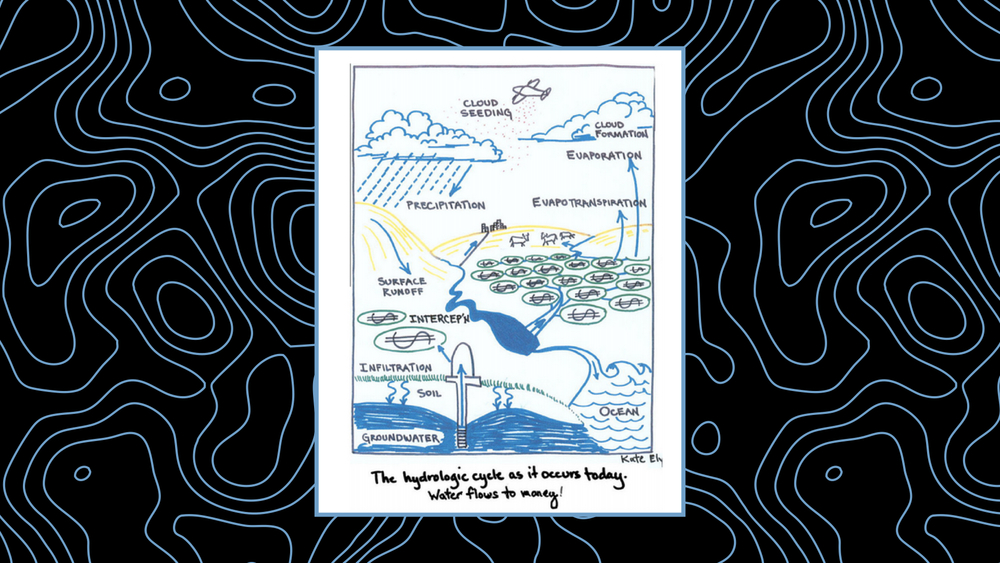

We’re all probably familiar with the Hydrologic cycle? To us, the idea of a “Hydrosocial Cycle” became a touchstone. Water, like oil or energy, doesn’t exist separate from our social and political systems, but rather, these systems make and remake one another — and us — over time. Can we change the ways that this happens, and maybe also change the impact we have on our environment, and vice versa?

Here’s a graphic that illustrates one instance of that in agriculture, how water doesn’t just move in the direction of gravity or evaporation, it actually flows toward money.

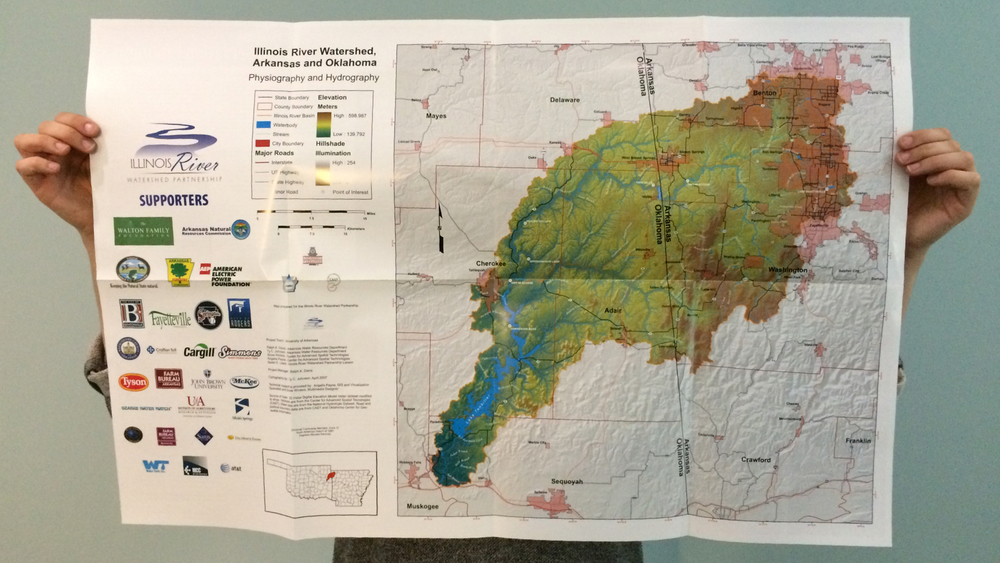

Not long after this first iteration of Water Bar we were invited by an art museum in Arkansas to install a version of the project as part of a national art survey exhibition called State of the Art: Discovering American Art Now. We had our hesitations (which I wrote about here) about participating in this project, but we ended up collaborating with the museum because they were able to link us up with the Illinois River Watershed Partnership, a nonprofit environmental advocacy group.

This is an image of the Illinois River Watershed, and on the left, the Illinois River Money-shed. To me, this image really represents a hydrosocial cycle. All the logos on the left are of corporations that have headquarters in and around Bentonville, most notably Wal-Mart. These corporations give money to IRWP and other environmental and community programs. They also have a disproportionate — and many would say negative — impact on the ecological and social health and well-being of that place.

We installed the project at Crystal Bridges Museum, which is an art museum created by Alice Walton, heiress to Sam Walton of Wal-Mart. Alice is the 13th richest person in the world, and also loves to collect and share American Art.

This is the installation that we designed and artist/fabricator Aaron Dysart built.We used the opportunity of this exhibition to highlight watershed issues, to promote watershed thinking, and also, to uncover what we now think of as watershed paradox.

We worked with our partners at IRWP to hire a group of college students with backgrounds in environmental science, business, policy, and architecture. Not one of them identified as a public artist when we began the project, but by the end of it, I think they all saw themselves as public artists — many of them even came up with their own new public art ideas.

These students were paid to tend the Water Bar for the duration of the exhibition, which meant collecting water every few days from surrounding communities and serving it to museum visitors. In the process, they also collected stories about those communities and the people who live there.

One of the people they met was Sherman, the water manager of a small town called Sulpher Springs, a rural community outside of Bentonville. Sherman had the job of water manager just like his father had the job, and although the water from this community was some of the best we served (it was from a deep artesian well that some say has healing properties) their public infrastructure was literally crumbling. Here we are investigating the broken wellhead housing.

We trained these students to be bartenders — inviting a real bartender and poet to teach them to pour flights and to make conversation. A poet because who better to help them listen for imagery and stories that would convey both the present and future? We also encouraged them to bring those stories about Sherman and the broken wellhead cover back to the visitors of Crystal Bridges museum. As they did, they started to ask questions.

Some said they felt uncomfortable taking the water for free from the community in Sulpher Springs and giving it to the visitors of the museum, many of whom came from other places and social class backgrounds. We encouraged them to make those questions part of their conversation at the bar, and also, to find a way to do something about it. For example, could they fix the broken wellhead cover?

To change everything, start anywhere.

Over the course of 6 months they served over 20,000 visitors, and the conversations they had were wide-ranging and rich, illuminating the state of our hydrosocial landscape in an era of Climate Change, growing inequity, water shortages, and environmental precarity. The students kept journals, reflecting on their own growth and learning, and also asked visitors to leave behind their own water stories for the project archive, which we have since incorporated into a Water Bar reader. If you ask them, ordinary people have a lot to say about how water shapes their lives.

As do some not-so-ordinary people. Here we are serving President Bill Clinton at the Water Bar. He told us about the role of water in the Middle-east Peace Process. He also cracked a few jokes with the man next to him, Archie Schafer, former executive of Tyson corporation. When he tried the water from Illinois River, Bill said, “So this is the water you polluted, Archie?” I laughed, and we’re laughing now, but it’s not really funny, right?

Side note, President Clinton also pardoned Archie while he was in office, keeping him out of prison for making illegal gifts.

In the bottom corner is Jim Walton and his wife, who we were surprised to learn drink their local tap water. Meeting them was wild, they are such down-to-earth people, and rely on the same water as everyone else. The Walton family gives a lot of money to environmental organizations, but at the same time, Walmart continues to expand their unsustainable project of outsourcing our pollution and exporting American consumer habits worldwide. Through campaign contributions and advocacy, both intervene in political process to make this system work easier for them… Water paradox, right?

For the students working behind the bar, this up-close glimpse of such complex systems intersecting was really a profound education. It was for us too. And while the Water Bar didn’t directly change any of those systems, it helped to educate and connect visitors to information and resources that are otherwise pretty obscure, and it did this by engaging body, mind, and emotion.

It was also a development opportunity for the student Water Tenders, young people just beginning their careers in business, policy, environmental management, and design. They learned new ways of talking to public audiences, and could begin to see the person-to-person connections that actually sustain our (broken) systems. They could also see themselves in the whole. That’s one step in changing everything.

Click here for a short video about the Water Bar project in Arkansas.

I could say a lot more about what we learned at Crystal Bridges, but unfortunately, I’m running out of time.

So I’ll just tell you that like a lot of our work, the research and development phase continues. We opened a Water Bar at the Northern Spark Art Festival this past summer, and 30 volunteers from local water utilities and non-profits served 2,000 people in one night.

We also created and distributed a newspaper and print encouraging people to consider the source of their water and how they can work to sustain its health and accessibility. I’ve brought some with me if anyone is interested.

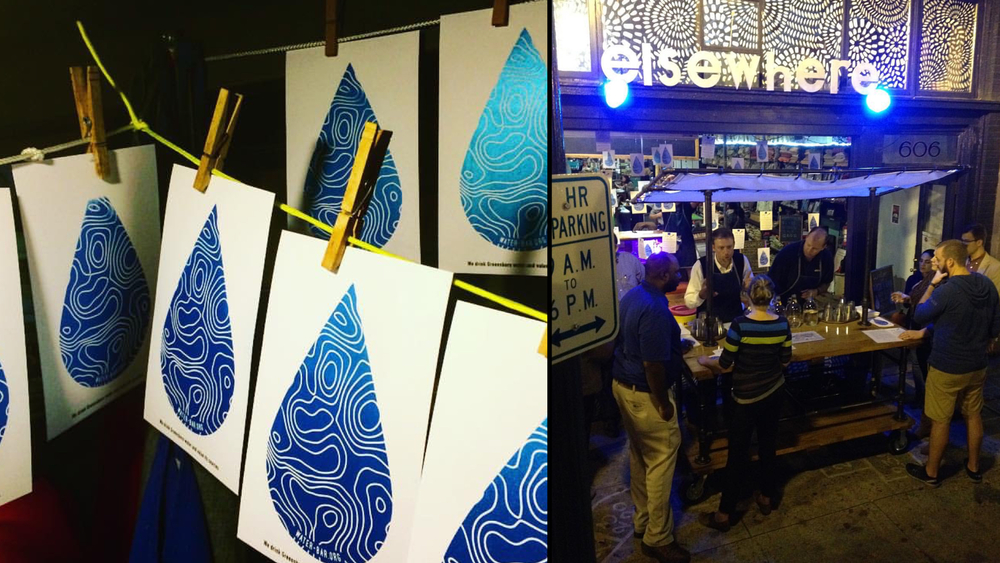

Earlier this month, Works Progress Co-Director Colin Kloecker opened a Water Bar in Greensboro, North Carolina as part of Elsewhere’s South Elm Projects.

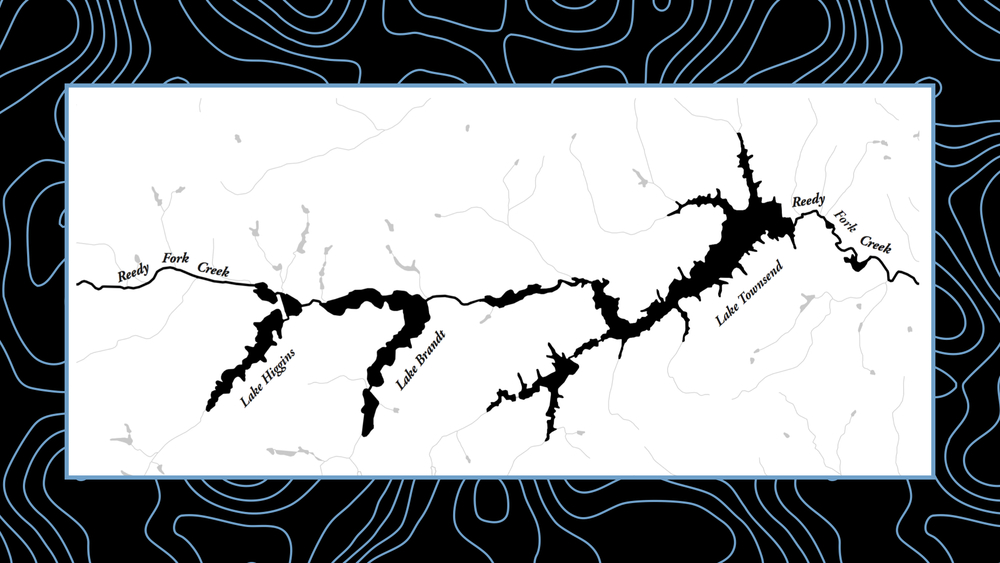

Colin collaborated with the City of Greensboro’s Water Resources Department and students from nearby Guilford College to serve water from these man-made reservoirs to the quickly developing South Elm Neighborhood. These groups and others will now use it as a launchpad for future water-related public engagement projects.

And later this spring we’ll be heading to San Antonio, Texas, to open a Water Bar that will bring together the issues and actors affecting Climate Change, Hydrofracking and Water Rights, exploring those systems through a history of ice and ice houses.

Meanwhile, we’re working on plans to hopefully open a more permanent Water Bar in a storefront in Northeast Minneapolis — a taproom for tap water — that would also be a collaborative public art and design studio, artist and scientist research residency, and exhibition space for collaborative art projects around local and global water issues.

As we continue to move this project out into the world through collaborations, we trust that it is helping people to see our water system as simultaneously complex, and comprehensible; As critical to their lives, and as something they can understand and impact. And at the same time, we are learning a ton about water.

I look forward to connecting with anyone here who might be interested in getting involved with these projects, or sharing their own ideas and resources.

—

Referenced Links:

Million Artist Movement | https://millionartistmovement.wordpress.com/

Works Progress Studio | http://www.worksprogress.org/

To Change Everything, an anarchist appeal | http://www.crimethinc.com/tce/

Public Art Saint Paul | http://publicartstpaul.org/

Water Bar | http://www.water-bar.org/

Video of Water Bar Prototype | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z0vTSHOm1lQ

Video About Water Bar in Arkansas | https://vimeo.com/113154274